Nicholas Anthony and Norbert Michel

Senators Bernie Sanders (I‑VT) and Josh Hawley (R‑MO) have proposed new price controls on credit cards. They frame the proposal as something that will give the public relief, but it’s hard to imagine “relief” is what people will feel if they have their accounts closed.

The Democratic socialist and Republican populist built their case for price controls stating that concerns about the restrictions are “backwards,” interest rates shouldn’t be based on risk, and that interest rates are too high. Let’s break down each of these ideas to understand why the senators are wrong.

“It’s Not Me That’s Wrong, It’s Everyone Else”

In their commentary for Fox News, the duo argues that economists “have it backwards” when they explain that price controls lead to shortages. They say, “Our bill would restrict financial institutions from charging working-class Americans exploitative and predatory credit card interest rates that can trap them into a vicious cycle of debt.” Such paternalistic policies may sound nice to some people, but their argument is far from compelling.

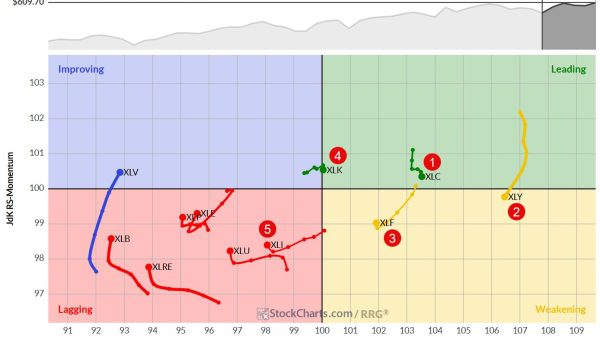

A good place to start is by explaining why economists say price controls lead to shortages. In a basic supply and demand schedule, establishing a price control—or a price ceiling—means that the amount of a good or service that people want (the quantity demanded) will suddenly be greater than the amount companies want to provide (the quantity supplied) at a given price (Figure 1). In economics, this situation is called a shortage. What exactly the senators see as being “backwards” here is unclear.

The risk of a shortage of credit is deeply concerning. At least one can choose to eat apples if there is a shortage of bananas. The same can’t be said for the people who are considered the riskiest borrowers and, therefore, pay higher rates. For them, a shortage of credit will likely mean losing access to credit completely. They may turn to family, friends, or other high-cost loans to bridge the gaps in their spending. Alternatively, they may pay bills late or skip payments altogether. And that’s not just economic theory; these problems are seen in practice as well.

“Different People Shouldn’t Get Different Rates”

Senators Sanders and Hawley also suggest that it’s a problem that “Big Banks can borrow money at less than 4.5% from the Federal Reserve” while “these same financial institutions are charging the average consumer 28.6% interest on credit cards.” From 30,000 feet in the air, these two cases might sound similar because they both involve one party loaning money to another. However, when it comes to how things work on the ground, these are vastly different scenarios.

The key difference is risk. The average bank has a robust history of borrowing, which serves to verify their creditworthiness. In contrast, the average person is likely to have a dramatically thinner credit file (or maybe none). Banks also have more assets than the average person. For example, a bank is considered “small” if it has less than $600 million in assets, but the median low-income American only has $900 in their checking account.

These differences only scratch the surface. However, these differences illustrate why it is misleading to suggest something wrong is taking place solely because one party is getting a lower interest rate than another party. Setting aside the differences between wholesale and retail pricing (an issue we will dive into next), interest rates should reflect individual risks. This flexibility allows the market to reach people no matter where they are.

“These Rates Are Just Too High”

The last argument to mention occurs throughout the commentary, where the two senators repeatedly describe interest rates above 10 percent as “exploitative” and “predatory.” They even accuse financial institutions of “extortion” and “loan sharking.” Setting aside the question of whether the senators have called for charges to be filed for these alleged crimes, it’s important to remember that value is subjective.

Consider what it takes to bring a good or service to the market. For lenders, covering the salaries of actuaries, navigating anti-money laundering regulations, and maintaining customer relationships is a costly process. Yet, running a business isn’t just about recouping costs. Lenders must also add value. Consumers will always want lower prices, but finding the right price means finding where both consumers and businesses are better off.

Whether it is $20 for a sandwich or $100 for a haircut, there will always be prices that are high for some people but just right for others. What’s important is that people can freely choose what is best for them and reject what isn’t. It’s through this process of bargaining and experimentation that countless people can vote with their wallets and constantly move the economy in a better direction by improving people’s lives. For the senators to impose their own beliefs would be to effectively override everyone else’s vote.

Free the Financial System, Don’t Restrict It

Expanding affordable access to financial services, looking out for the best interests of others, and creating a level playing field for competition are all worthy ideals. A market economy is the best way to achieve those ideals fairly. Price controls, however, achieve the opposite of these intended effects. If Congress wants to improve the financial system, it should look to removing the legislative and regulatory burdens that have been weighing it down.